Whether it be paella or revolution, nothing that is Spanish is ever simple.

-Henri Verneuil, ‘Un singe en hiver’ (1962)

I’ve lived and traveled in many parts of the world, but the biggest culture shock of my life was moving to the United States for college from my hometown of Miami. That’s right, Miami wasn’t then, and certainly isn’t now, part of the ol’ US of A, but something else altogether.

I remember the first time I realized I was a foreigner in my country of birth.

A month into my first term at a large midwestern university, I got an invitation for a banquet meal in honor of the recipients of some bundle of free cash I’d been awarded. I vaguely remembered having accepted it, but had assumed it was due to grades or SAT scores. Somewhat mystified, I put on that blue blazer most of us had in college (the one with the jingly brass buttons), and headed to the Alumni Hall for the free chow.

I looked around. Most of the other guests were either Black or Mexican-American in what was and is a very white Midwestern state. As I sat there eating the chicken dinner, and after some interesting chit-chat with my neighbors whom I found as exotic as they apparently found me, it finally dawned on me: Oh, I see….apparently I’m some sort of minority now or something. These people think of me as some sort of Other, and this whole song and dance is part of that Othering.

I had been put in a box, a box I didn’t even know existed before that moment. That’s just how foreign Miami was: I didn’t have even an inkling of mainstream American racial politics.

It took years to really sink in, and even much later during grad school in the Bay Area, I hadn’t yet grokked where Hispanics fit into the American pecking order (particularly in a California where that pecking order was rather different than Miami).

To a Miami son-of-Cuban-exiles, the thought that I would somehow qualify for special assistance was an utterly foreign notion that never even hit me until that scholarship dinner. Why would I have thought myself a minority? In Miami, everyone from the mayor to the wealthiest tycoon to the police officer who stopped you was Cuban. The city itself was a suburban reboot of pre-revolutionary Cuba, down to the Jesuit school I attended—our most famous alum: Fidel Castro—which had been ported over to this side of the Florida Straits like every other institution and opinion from the exiled Cuban bourgeoisie. Anglos seemed foreign and almost rustic by comparison, outsiders in a city that was fast becoming the business and media nexus of Latin America.

In my childhood you had a coalescing Cuban diaspora in an otherwise provincial city whose biggest trade was illicit drugs. But by my adulthood you had Venezuelans fleeing Chavez, Brazilians seeking boltholes with good shopping, Argentinians fleeing a currency crisis, Columbians seeking stability from narco-marxist violence, and just about every other flavor of South American. Suburbia exploded horizontally out to the Everglades, the downtown skyline rocketed vertically upwards with shining glass towers, while the city just got more and more broadly Latin American.

One day, it suddenly seemed like every upper-middle-class LatAm family had a bank account and a condo in Miami, and was sending their kids to FIU (the local state university, highest foreign enrollment in the US). Miami had gone from a provincial city of refuge to a cross between Vancouver and Singapore, but for Latin America instead of China.

Miamians are a pushy, opinionated lot (Cubans in particular), and if you didn’t like the Latinization of Miami from a sleepy beach town to a cosmopolitan entrepôt, the locals didn’t hesitate to tell you where the turnpike to Orlando or Atlanta was. And many Anglo Miamians, particularly the old Florida crackers who’d settled the place, disappeared north up that turnpike, never to return.

Which is why I was unsurprised with the election news about how Miami Cubans had broken ever harder right than usual, helping secure Florida for Trump. It’s exactly what I would have expected, though The Times seemed somewhat befuddled by the whole thing (I’ll be QT’ing them liberally, pun intended).

Like it or not, while politicians may trumpet the finest members of their political tent to supporters, they’re also liable for the worst members, at least as perceived by their enemies. Just as Trump was pegged as at least passingly sympathetic to, if not outright supportive of, white nationalists with his failure to renounce their sordid lot during the Charlottesville tragedy, the same dynamics hit Biden with his political coalition. I’m afraid you can’t quite have the Bernie wing inside your tent without that rhetoric coming to signify your candidacy, at least partially, to those who view such tendencies with suspicion.

To be blunt, Miamians have heard this populist socialist rhetoric before: university-educated radicals rallying the working classes against the oligarchic upper classes, in the name of lofty and vague ideals that require a political revolution to implement, while accepting some urban violence as the cost of doing business. It’s the rhetoric of the Latin American Left—and many of the Hispanic voters of Miami wanted nothing to do with it.

In a society of pure spectacle, aesthetics determine every allegiance, whether consumer or political. The fact AOC wasn’t running in Florida (a common retort to the coattails thesis) fails to grasp that in our new media era, politics are now entirely a consumer-branding exercise, one at which politicos like AOC excel. It’s your brand on the ballot, not a concrete public-policy platform. Further proof: It wasn’t just Biden that lost in Miami, just about every major Democratic politician down the ticket lost too. Miami-Dade is now a purple county again; political signals just don’t come any clearer than this.

Part of the surprise at the Miami vote may have come from the somewhat contrived ‘Latino’, a term that often obscures as much as it clarifies.

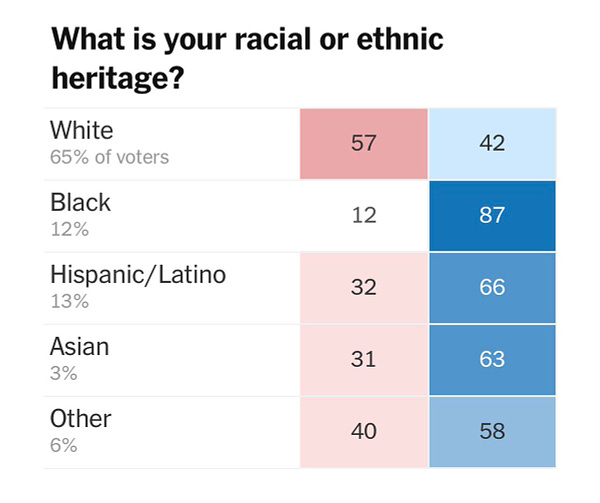

In her exasperated tweet above, Nicole Hannah-Jones captured well the artifice behind the label. Miami Cubans don’t vote like Mexican-Americans or Puerto Ricans, and the various sub-groups have little in common other than a vague cultural commonality. ‘Latino’ is effectively an invention, one even those thusly labeled don’t necessarily accept. In the 2010 census, millions of Hispanics switched from the ‘Hispanic/Latino’ to ‘white’, many more than went the other way.

And why wouldn’t they? Latin America presents as vast and varied a racial spectrum as the United States, if not more so. Despite what many progressives seem to think, minorities don’t just sit there stewing in their Otherness all day, like some sort of personal obsession. The otherness implied by ‘Latino’ only makes sense within the Anglo context (cf. me trying to figure out my scholarship dinner). To the extent Hispanics think about race at all—and it’s way, way less than Anglos do¹—matters break down very differently than they do in the United States.

Which brings us to the other 2020 Hispanic election surprise: the Texas border region.

La Línea

The other ‘Latino’ shock of the election was the Texas border counties that flipped or otherwise showed huge GOP gains, sometimes more than 30%(!), in counties that are heavily (meaning close to 90%) Hispanic.

For starters, the much awaited blue-ing of Texas (which I wrote about during the midterms) didn’t happen: Trump captured about the same fraction of the vote as he did in 2016. Even more importantly, the Democrats did not capture the Texas House despite strenuous efforts to do so, which is absolutely critical for one reason: the House determines the state’s districting (AKA gerrymandering) and this is a census year. As in 2000 and 2010, redistricting is likely to keep Texas a bright-shining red, save for urban enclaves, for another decade to come.

And that thick band of red along the border in the below map? Firstly, concerns about the energy economy in the area drove much voting: Biden’s comments about eventually shuttering the oil industry in the debate did not go over well. And after that, the usual laundry list of typical political concerns, little distinguishable from other GOP voters: jobs, gun rights, jobs, abortion, jobs, religion, and once again, jobs. What most stuck out due to its absence in all these “why’d these counties go red?” pieces is the overarching issue that supposedly obsesses the Hispanic voter: immigration.

Let’s pause for a moment and confront some of the Wrongthink that colors much mainstream thought here.

Being a proper progressive these days requires maintaining two central ideas without any hint of contradiction:

The United States is a racist, sexist, colonialist hellhole of a country that can’t do anything right, and must be constantly derided and unflatteringly compared to such obvious analogs as small European ethnostates.

We must maintain completely open borders and accept any and all immigration from any country, many of whose populations are desperately trying to enter the US despite self-evident point #1.

This absurd contradiction, within the context of this conversation, only exacerbates the issues with mainstream thinking about Hispanics.

For starters, people who have done anything and sacrificed everything to be in the United States clearly aren’t buying into point #1. There were at least as many American flags as Cuban ones at the Miami Trump rally pictured in this essay’s cover photo. Hispanics are the fastest-growing segment of military enlistment. Hispanics believe in the reality of the American dream, and that their children will have better lives than them, far in excess of the American average. As with many immigrants, Hispanics possess the convert’s zealotry, and are quite pleased by the US and proud to be a part of it.

The fashionable oikophobia of the Vox-reading class—whose coddled brains would melt if they had to endure what the average Cuban does to get by under broken-down communism—gets no play in these parts. The biggest vote Hispanics in America have made is the one in America itself: the vote you make with your feet is the truest and most important of all. So those who relish in criticizing America and swearing to one day leave might reconsider their messaging to those grateful they went the other way.

(The following tweets are from @Chris_arnade, one of the few urban elites—”front-row kids”, as he calls them—who’s spent time documenting the realities of America’s oft-ignored social groups. I’m citing them here as anecdotal talking points to broader trends, and because I like Arnade’s work.)

To understand Miguel doesn’t require a deep reading of Octavio Paz’s El Laberinto de la Soledad and a voyage to the heart of the Mexican soul, but rather a very basic sort of human empathy, and the ability to see the world through the eyes of a working-class father and his aspirations for his family’s future. Miguel doesn’t know or care about ‘LatinX’, this preposterous invention that can’t even be pronounced in the language of the culture it purports to represent. He cares about safe neighborhoods and good schools for his kids (per Pew, the economy was the number one issue for Hispanic voters, with violent crime and healthcare higher than immigration). As a citizen in a democracy, he’ll vote for politicians who promise and hopefully provide that, rather than those that preach some half-baked gospel about ‘defunding the police’ in the face of urban chaos (much of it driven by those same liberal whites).

On to point #2.

Despite what the bien-pensants might imagine, not every argument for controlled immigration and border security makes everyone with an ‘o’ at the end of their first name collapse into a seizure of fear and rejection. A political class that’s been listening to the “they’re not sending their best” Trumpian soundbite on constant repeat for four years somehow thinks that’s the entirety of the Hispanic conversation around immigration. In fact, 73% of Hispanics think the country has either the right amount or too much immigration, and only 14% indicate there’s too little immigration. While Hispanics do cite immigration as one of their top 10 issues of concern in elections, they are not a single-issue polity on the topic, nor are they universally on one side of the debate.

The related question around border security, as with ‘Blanco’ above, is also complicated. Border residents, many of whom are Hispanic, are very concerned about border security, even if they’re not fans of Trump’s disruptive wall. Of course they are. Many Hispanic immigrants know what lies on the other side of that border, it’s precisely what they came here to escape. Insofar as that means threats like crime or drug cartels, they want nothing to do with it, as would anyone if their backyards backed into Mexico (instead of say Prospect Park).

Only from the all-look-same perspective of the Anglo mainstream would American Hispanics, many of whom have been here for generations, somehow reflexively consider themselves in the same boat as undocumented migrants coming across the border. They don’t of course, anymore than Asian-Americans necessarily cast their loyalties with the Chinese government. “I’m Hispanic, but I’m American,” says Elizabeth Lazo, a Democrat-turned-Trump-voter in Starr County, TX, shrugging at what might seem a conflict to outsiders. Or to quote one Mexican-born Border Patrol agent Vicente Paco, interviewed by The Guardian: “Heritage is not to be confused with patriotism.” What stronger statements of America’s unique creedal nationhood, which overrides the primitive attachments of tribe and ethnicity, are there than those? And who’s indulging in racial essentialism by lumping everyone with a surname of ‘Martínez’ into one big simplistic bucket?

To briefly touch on another area where common perception among Democrats veers from reality, Hispanics are religious, very religious. At 83%, Hispanics claim the highest rate of religious affiliation among all US ethnic and racial groups, majoritarily Catholicism. Which leads to another left-wing schism: Over half of US Hispanics believe abortion should be wholly or somewhat restricted. That’s not surprising, as Catholicism prohibits abortion and the practice is either illegal or highly-restricted in most of Latin America. This doesn’t quite jibe with the current Democratic Party either, as anything even vaguely non-pro-choice is anathema on that side of the political aisle. What’s the party going to do about that?

‘Diversity’ is all fun and games, until you actually get some real ideological diversity, and then suddenly you realize the whole thing is more than just taco trucks and reguetón. Or as William F. Buckley so memorably put it: “Liberals claim to want to give a hearing to other views, but then are shocked and offended to discover that there are other views.” You cannot have members of a different culture and religion integrate into your society as full-fledged citizens, citizens with a political and economic voice, and not have those views manifested somehow in your politics. Hispanics simply won’t take ideological dictation from the current batch of elites. If you somehow imagined the ‘browning of America’ necessarily meant an electoral boon to the Left, then you possess a parochial view of the Spanish-speaking world.

“Remember the Maine! To hell with Spain!”

The whole ‘Latino’ debate is really the most recent installment in a centuries-long struggle between the Anglo-Protestant and Hispano-Catholic worlds and their colonial offshoots in the Americas. The story starts with the Spanish Armada’s attempts to invade the British Isles and the bloody occupation of the Spanish Netherlands, continues on through the Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War and the Spanish-American War, and ends in our modern era with Bay of Pigs, “wet foot, dry foot”, Reagan’s amnesties and so on and so on. The two civilizations have been at each other’s throats while also intermarrying and either pushing into or otherwise making off with each others’ land for half a millennium now. This round of fashionable identity politics and election-season Twitter spats are but one tiny emanation of a much bigger story, a story that the Anglo side of the conflict, as the historical victor, has the luxury of mostly forgetting or defining in their terms.

Such is American imperial privilege: The empire’s inhabitants need never confront the limits of their worldview, and even cultures and nations outside their purview exist only as projections of their internal neuroses. Talk to your standard Berkeley liberal about Cuba, a mistake I made more than once while studying there, and you soon realized that Cuba—Cuba the beautiful, Cuba the enchained, Cuba the forever lamented—existed as nothing but a talking point in that person’s pissy political monologue. They no more cared for Cuba itself and its people than they did the moon: the country was just a walk-on extra in their political drama where mainstream white elites, either progressive or conservative, were really the main show.

Until of course, an election such as this one, when the ‘LatinX’ extra speaks a few unscripted lines on-stage, and suddenly the dueling elite protagonists turn in horror at the dramatic upstart somehow stealing the spotlight. Much panic-tweeting ensues.

The problem with basing a political platform on white guilt is that, at some point, you run out of either whites or guilt. Which is what happens in a truly majority-minority nation when non-whites (at least as currently defined) assume their equal place in the economic and political firmament. The Diversity Industrial Complex’s first move, when faced with the paradigm-shattering development that their dualistic worldview is insufficient, is to redefine ‘white’ to include the more successful of the new arrivals (as happens with Silicon Valley employment stats and Asians).

But how long can you maintain that strained narrative when the person uttering tropes about the white/POC duality is historically Punjabi or Colombian? What is Anand García-Hsieh, a hypothetical tech worker in our not-too-distant mixed-race future that resembles Brazil more than anything, going to say about POCs? Right now we’re all reciting the often fanciful racial narratives conjured by out-of-touch academic and media elites, but for many of us it’s getting pretty damn old already.

Consider Congressman Ruben Gallego, an Hispanic Democrat from Arizona, where the Hispanic vote flipped the other way from Texas and Florida:

In another tweet, where Gallego also rejects the LatinX label, he cites the key to electoral victory having been a constant engagement with the Latino working class by those who understand it. Once-every-four-years livestreamed visits to the local taquería and the odd rhetorical pat on the head just don’t cut it anymore.

As Swiss novelist Max Frisch wrote about Turkish immigrants in Europe: “We wanted workers…but we got people instead.” Ditto Hispanics, who now constitute over half of this country’s population growth, and aspire to be more than cutout characters in a mainstream political drama that largely doesn’t take them seriously. Given the vagaries of our electoral college and the apparent demographics, it’s inevitable that sooner or later they will be.

Ronald Reagan famously said: “Hispanics are already Republican. They just don’t know it.” Based on this election, not to mention the social conservatism of Hispanics, Ronnie wasn’t totally wrong. If the Democratic Party continues its leftward drift and flirtation with socialist rhetoric, as well as being utterly disconnected from real-world concerns around law enforcement and border security, ‘Latinos’ might just realize where they really stand in the American political duality. The Hispanic world, in all its sweep and variety, is a lot more than just salsa music and tacos, or knee-jerk opinions about immigration policy. As has happened countless times in the shared history of these two cultures out here on the American fringes of the Western world, we’ll have to find some way to live with each other or suffer dramatic consequences.

The Anglo world is just a lot more race-obsessed than the Hispanic world, with bizarre notions of racial purity, such as the one-drop rule, and a convoluted moral ontology. The only English-language equivalent to the Spanish ‘mestizaje’ (a word of neutral or even positive connotation) is the word ‘miscegenation’, a word of decidedly negative connotation used exclusively by segregationists. Americans still agonize over the difficulty of interracial marriages even now, an issue that was considered settled in 17th-century Cuba. Race is just this immense Anglo American hang-up that even Hispanic new arrivals can’t quite manage to escape: they’ve got to decide on a racial label for themselves too, even if it’s largely nonsensical.

So...everyone agrees? :)

"Border residents, many of whom are Hispanic, are very concerned about border security, even if they’re not fans of Trump’s disruptive wall."

You could not be further off the mark. Guy from Brownsville here, living 1.5 miles from the river as the crow flies, and I feel very safe, and I haven't heard a soul say border security was a concern. No one. People have been living next to the river forever, and only within the last 15 years has there been a patchwork quilt of fence. Hell, there's even a golf community full of white retirees right on the river, "unprotected" by the fence.. And within the border cities themselves, violent crime is below the national average. "Border security" is not in the average person's vocabulary over here.

About the rest of your analysis of South Texas, you point out some correct attributes, but I think your analysis along with many other commentators' analyses is really just foisting pre-conceived notions onto this region and Latinos in general. People look at Starr and Zapata, and they say, OMG, Latinos are abandoning Democrats. Zapata had 4k voters and Starr had 17k. Nearby Hidalgo and Cameron counties are where most people live (330k voters). Let's just look at my county, Cameron. Biden got 56% and Hillary got 64%. An 8% gap doesn't look as bad, does it? Now consider mail-in ballots. We have no idea yet how many ballots didn't make it to the elections offices. Those that were accepted went for Biden by 70%. Then, you have to consider that Biden, compared to Hillary and Obama, has no star power with Tejanos. Trump also had a really good social media campaign targeting conservative non-voters. This is really a story of dampened Democratic turnout and increased Republican turnout. But commentators make it seem like Tejano Democrats flipped. Certainly, some did, but there were also Republicans who flipped for the presidential race, so it's a wash. Just took a really quick look at the precinct reports from 2016 and 2020, and Republican precincts were less Republican and Democratic precincts were less Democratic. Still need to look into that further, but I'm just saying the real story is a lot more complex then what most commentators are thinking. But one thing's for sure, the idea that Tejanos are abandoning the Democratic party is way off.