This is the first in a two-part series on privacy and Web 3. Next week, I’ll continue my riff on the origin of modern conceptions of privacy.

Therefore whatever you have said in the dark shall be heard in the light, and what you have whispered in private rooms shall be proclaimed on the housetops.

-Luke 12:3

Web 3 is the reverse of web 2 in severals ways, and that ‘flippening’ can be disorienting

Take the usual ordering of consumer usefulness followed by monetization, as one clear example.

In Web 2, you first find a viral consumer use case and then, often much later, find some way to pay for it. Meanwhile, you float the company with speculative capital from VCs. As late as the time of Facebook’s IPO, the ads system was a mess and did not generate the sort of revenue growth that justified the company’s massive valuation. The second half of my memoir Chaos Monkeys documents just that mad (and successful) scramble fix the company’s broken monetization.

In Web 3, companies achieve liquidity early via ‘tokenomics’ and other novel mechanisms to raise capital from users (often highly speculative in nature), and build the necessary technical infrastructure to create an alternative internet: decentralized servers, identity-management ‘wallets’, token exchanges allowing easy movement among various ecosystems, etc. The viral consumer use case (if there is one) comes much later, much to the derisive trolling by the latest wave of crypto-skeptics.

Some Web 2 companies like Uber still aren’t profitable, years after their founding and having gone public. We used to find this odd—trolls are nothing new and they railed against the early Web 2 companies too—but now we’ve simply gotten use to it. Web 3 has yet to prove out its flipped model for utility vs. speculative value.

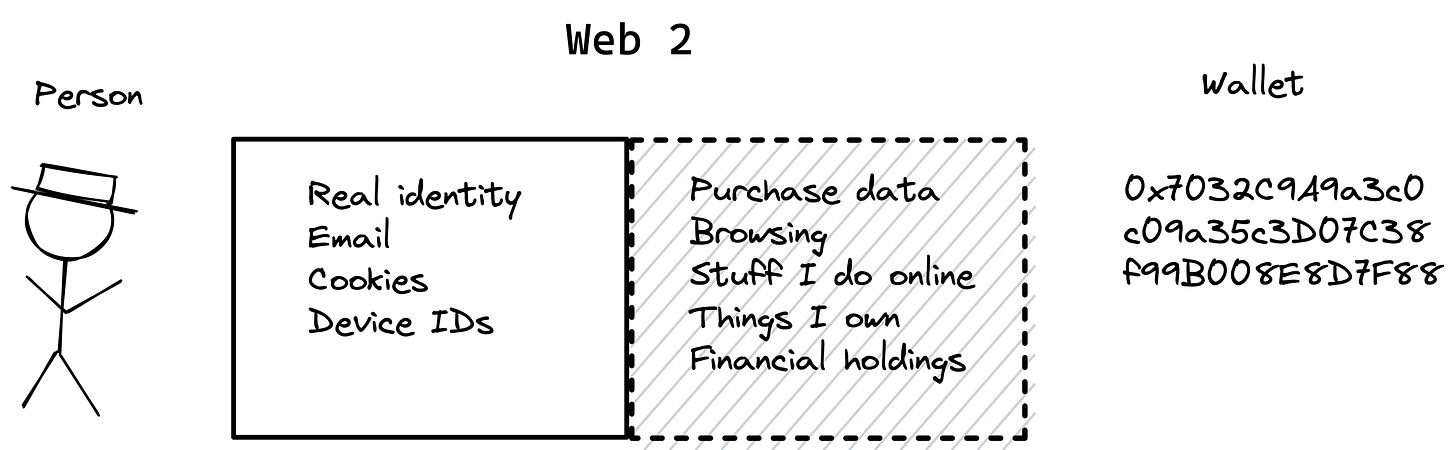

The question of data privacy suffers a similar flip between Web 2 and Web3, reversing many long-held assumptions in weird and novel ways.

In Web 2, thanks to the tireless efforts of the growth teams at companies like Facebook (plus our own human addiction to virtualized socializing), most everyone save anon-account shitposters is perfectly comfortable with living their lives fully publicly and online. What we don’t like in Web 2 is having what we do—what we buy on Amazon; where we stay on Airbnb; what we browse or buy online—being made public. Everyone may know our locations and the faces of our family, but if anyone figures out that I streamed Parasite last night or bought a pair of size 43 Birkenstocks, I want EU aircraft to strafe their homes.

Conversely in Web 3, absolutely everything I do ‘online’ (whatever that means now; what do we even do anymore that isn’t online in some form or another?) is public and immutably recorded for all to see. Imagine for a moment Web 2 worked that way: every time you bought something at Amazon, the company broadcasted it publicly, tweeting it out perhaps. ANTONIO BOUGHT A JUMBO PACK OF SUPPOSITORIES. HAHAHAHA.

You (or I) would be outraged. Yet that’s what happens every time you buy a NFT from OpenSea or plunk a pile of money into decentralized exchange UniSwap. It’s broadcast in the most indelible way possible, in a way that no GDPR privacy law will ever be able to do anything about. Somehow, everyone in Web 3, including and especially the privacy crypto-bros, are on-board with that plan.

Their only stipulation is that the unique identifier tied to all that activity (the wallet ‘address’) is never tied to anyone’s persistent real-world identity. Like the revelers in a masked ball of yesteryear, so long as the masks aren’t removed, all is well.

What can possibly explain this utterly different framing for notions of privacy among old and new versions of the Internet, particularly with the small (but growing) set of users who participate in both?

One helpful concept comes from the academic world of philosophy: Helene Nissenbaum’s ‘contextual privacy’ is a formal theory of privacy considerably more sophisticated (and adaptable) than the moral absolutism that tends to dominate the privacy discourse. An example she draws in her work is imagining your interactions with your physician when dealing with a medical issue. Even in a world where the right to live as a stranger among strangers reigns supreme, we unquestioningly turn over the most intimate medical details to people we barely know. With full consent from us, our physician sends off millimetric images of our skulls and organs to remote radiologists who inform you whether you’ve got terminal cancer or not. We do that because, aside from wanting to know if we’ve got cancer, we feel protected by a strong regime of HIPAA legislation plus a professional code of ethics that stiffly constrains everyone involved in the data chain, from nurse to surgeon.

Our species was never meant to be in instant conversation with billions of other humans. Absent a Luddite jihad that destroys the digital nervous system locking us into global waves of emotion around the next ‘current thing,’ we’re going to invent new norms to make the inhuman slightly more livable.

Now, let’s imagine you leave your doctor’s office and fire up Instagram to take your mind off the diagnosis he just gave you, which is that you don’t have brain cancer but you simply suffer from chronic migraines and will just have to deal. Scrolling past pictures of friends and celebrities, you see an advertisement for a migraine medication, specifically for the vestibular migraines you suffer from. While two seconds ago you were willing to send images of your brain across the world for medical advice, you now feel horribly violated knowing that everyone from Facebook to a pharma marketing team know about your condition. The context of your privacy—what’s being revealed to whom and for what reason—utterly changed and you had no say in it.

The challenge before us is to figure out the ground rules of privacy in Web 3, where the ‘contextual privacy’ that has shaped both user expectations and government regulation in Web 2 no longer hold at all; in fact, they’re utterly fipped.

Those who can’t innovate, regulate

To illustrate just how flipped they are, let’s review the basic tenets of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the regnant standard in data privacy (and somewhat emulated in American standards like the California Consumer Privacy Act).

There are two foundational concepts in GDPR: the presence and persistence of ‘personal data,’ and who keeps data around.

The latter is divided into two classes of data hoarder: “controllers” and “processors.” These categories roughly map to ‘first party’ and ‘third party’ distinction made between (say) The New York Times (which you visit and subscribe to), and the web analytics package they use to measure how long someone stays on their website. Ultimately, The Times is the real owner of this relationship, who both needs to get an opt-in and face the music if found in violation. Their analytics software is merely a data orderly.

Who’s the data controller of the blockchain? Who even owns things like Bitcoin and Ethereum? The short answer is nobody and everybody; everybody in this case is the thousands of nodes that do the ‘mining’ and verification of the network, making sure transactions are legitimate and collectively keeping all the network state around. If your personal data makes it onto some public blockchain, it’s likely on many machines spread all over the world, with no singular entity able or willing to take the ‘controller’ liability bullet1. That’s the ‘nobody’: there’s no ‘real or legal person’ the EU can nail to the wall for not deleting data or whatever else their precious GDPR stipulates.

Speaking of deletion, just what is this ‘personal data’?

The definition seems almost intentionally vague, with every practitioner coming to their own talmudic interpretation. Per the letter of the GDPR, personal data is “an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.”2 In other words, it’s things that can be traced unambiguously to the real you, and reveal something juicy about you, whether your address, medical condition or your taste for Penelope Cruz movies. Along with this vague-seeming definition, there are all sorts of restrictions around user deletion power (the ‘right to be forgotten’), obligatory opt-in prompts, and the necessity to minimize the scope (and spread) of personal data.

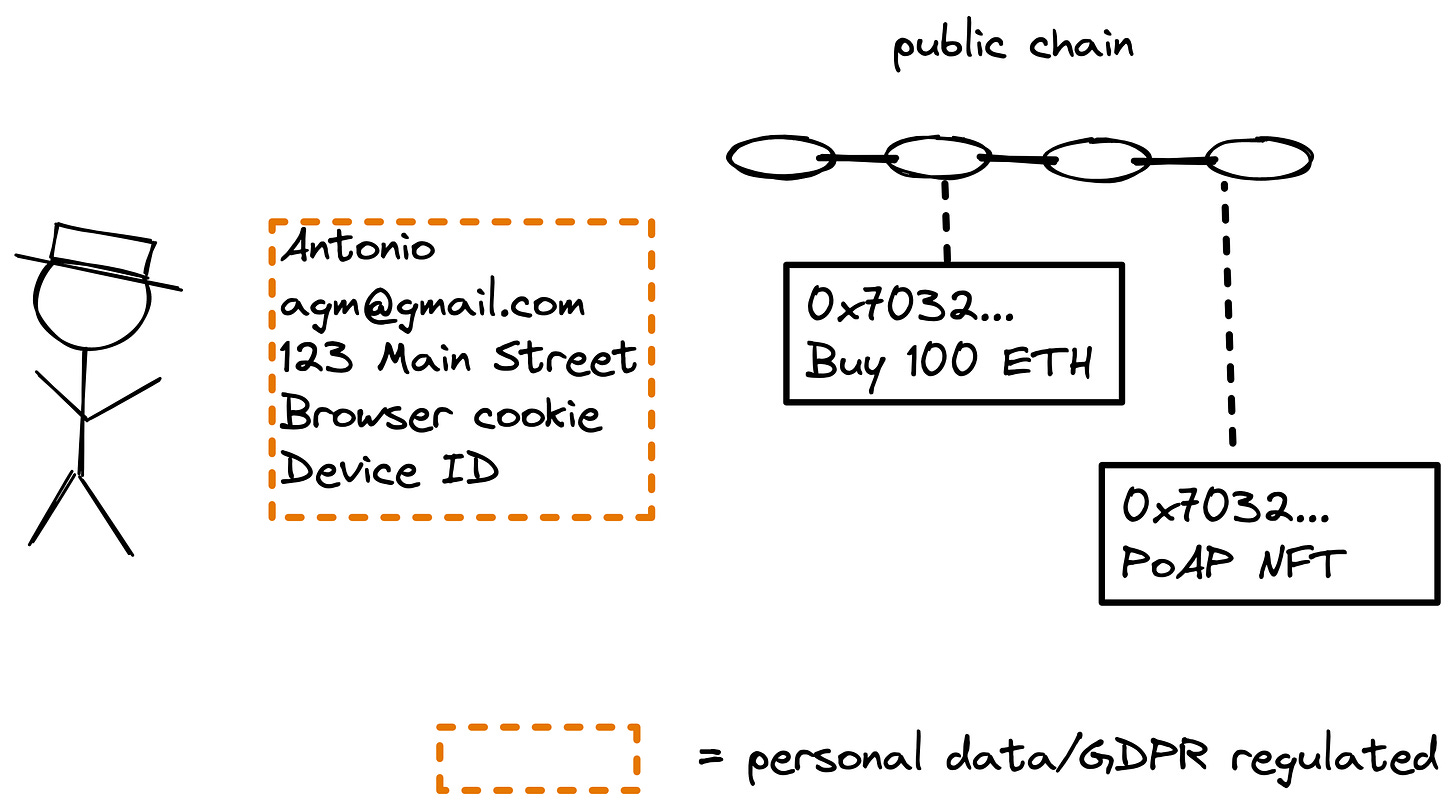

Goes without saying that putting any personal data on a public blockchain violates both spirit and letter of the GDPR. If nothing else, the sheer immutability of blockchain data—you can’t delete a block without redoing the chain, something semi-impossible in practice—puts it in obvious violation3. We’re going to have to get creative if we’re going to build privacy-compliant apps on the blockchain, particularly ones involving any user targeting or attribution.

One leap of creative interpretation is that behavioral data like transactions (which lives in a bit of grey zone in GDPR) are only personal when linked to an actual real person. In the absence of the real you, Amazon keeping what some anonymous individual purchased is not obviously regulated by GDPR. In fact, there’s a loophole for keeping data necessary to run a business, such as revenue data to calculate taxes.

Extending that to the chain, so long as the wallet is unassociated with real personal data, either on chain or off, it shouldn’t be subject to the many data restrictions of GDPR by a strict reading of it. Even if you don’t buy the argument, there’s essentially no way to comply with GDPR with on-chain data, other than not putting egregiously personal data (like user information) on chain to begin with.

Well, what happens when you do associate a real person to a wallet, and all the behavioral data that implies? That happens routinely when a DeFi company like Coinbase does regulatory Know Your Customer and actually verifies your identity, or when a game developer (say) associates your wallet to personal login information like an email. This will sound odd, but that linking of an entire blockchain rap sheet to a person suddenly makes that wallet be personal data. The holder of the join to the real person can indeed profile the user based on blockchain data (even if nobody else in the universe other than the user knows this wallet corresponds to that user). The controller in this case, i.e., the entity that can join a wallet’s data to a user, is absolutely responsible for that join only they own; their GDPR responsibility lies in deleting the join that makes the profiling/personalization of on-chain data possible, even if deleting on-chain data is itself impossible.

Why such jesuitical acrobatics?

Let’s go back to Nissenbaum’s contextual privacy. The only way to reconcile the Web 2 privacy context of GDPR (which considers identity public but data private) with the Web 3 context of blockchains (where identity is private, but data public) is to merge the contexts when the data does the same. In other words, merging identity and data makes both subject to GDPR compliance, even if the data was anonymously public before you joined them. Once you delete that join to real identity, the data goes back to simply being anonymous and private. This is odd to Web 2 ears, but again, it’s the contextual expectation in Web 3. The entity on the compliance hook is whoever owns the join, a join that only happens because of a first-party relationship (and opt-in) with the actual user. This is about the only way to square this Web 2/3 context circle.

Of course, it means that any such personalization of blockchain data must live with a single entity (or at most a processor-type subordinate): you can never decentralize real identity on the blockchain. But that’s fine. This is one area where you absolutely do not want ‘trustlessness’ to define how data moves around.

If this all sounds like medieval schoolmen debating the physical dimensions of angels, it’s not an inapt comparison, but a lot of privacy thinking is contrived and convoluted.

Privacy, the invention

The word itself ‘privacy’ doesn’t appear even once in the American Constitution, and as a legal principle, it wasn’t until 1890 that Louis Brandeis formulated it in a way we would recognize today. The spark for Brandeis’ historic treatise was the sudden emergence of the telegraph and portable cameras; more specifically, his socialite law partner Samuel Warren was getting written up in the gossip rags, complete with paparazzi photos.

Once again with Web 3, some newfangled contraption is forcing us to rethink what it means to live among a world of strangers, safeguarding our inner worlds lest they be ‘proclaimed on the housetops.’ Our species was never meant to be in instant conversation with billions of other humans. Absent a Luddite jihad that destroys the digital nervous system locking us into global waves of emotion around the next ‘current thing,’ we’re going to invent new norms to make the inhuman slightly more livable. It’s what we’ve always done.

And forget complying with the GDPR’s restrictions about moving data overseas: that’s yet another unsatisfiable condition.

The law itself is surprisingly readable and worth a look.

Some would make the argument that encrypted data on chain is no longer ‘personal’ from the GDPR perspective. That’s the argument of blockchains like Monero or ZCash which reveal almost nothing about the nature of transactions on their chains, not even wallet addresses. Even if it’s not on those chains, your personal data can be put on-chain but encrypted, and then the private key destroyed as a means to ‘delete’ it (i.e. make it functionally unreadable). Or you can link to off-chain personal data, and simply take down that instead. It’s not clear yet what the EU thinks about these workarounds and whether that’s ‘deleted’. Apparently, the UK is on board.

Is Facebook turning into Yahoo of Web 2?

In my experience, GDPR and CCPA are both minimally enforced save for some digital ambulance chasing lawyers. And IMO the "need" for such regulation seems to stem back to some sort of elitist hatred towards Tech for making boatloads of money, but maybe I am wrong and consumers actually care? In any event, you talk about the "gray areas" of GDPR, you make the very apt point about the difficulty in defining ownership of data, and the whole custodial/honor system problem of deleting joins... and I wonder.. is this ambiguity the sort of Trojan horse that big G uses to drive a wedge into the whole crypto shebang.. or does privacy regulation blow over (as Chamath would say) as "a big nothing burger"?

Looking fwd to next week