Third Time as LARP¹

Bruno Maçães and American magical realism

Following ‘Pull Request’ tradition, this is a companion piece and book review to our interview with author Bruno Maçães about his new work History Has Begun: The Birth of a New America.

Ours is indeed an age of extremity. For we live under continual threat of two equally fearful, but seemingly opposed, destinies: unremitting banality and inconceivable terror. It is fantasy, served out in large rations by the popular arts, which allows most people to cope with these twin specters.

-Susan Sontag, ‘The Imagination of Disaster’

The opening passage in yet another book about society’s simulacra, Mediated by Thomas De Zengotita, features the narrator stuck with a broken-down car in the wilds of Saskatchewan. There, De Zengotita experiences what almost none of us do anymore: reality unmediated by representation.

You are so not used to this. Every tuft of weed, the scattered pebbles, the lapsing fence, the cracks in the asphalt, the buzz of insects in the field, the flow of cloud against the sky, everything is very specifically exactly the way it is—and none of it is for you. It isn't arranged so that you can experience it, you didn't plan to experience it, there isn't any screen, there isn't any display, there isn't any entrance, no brochure, nothing special to look at—whatever is there is just there, and so are you. And your options are limited. You begin to get a sense of your real place in the great scheme of things. Very small.

For De Zengotita, the opposite of reality isn’t illusion per se, it’s the optionality of ignoring reality, of changing channels when the show becomes unpleasant or boring and, like a video-game character, hitting the respawn point for another go. Life inside the cave of representation is a flattered one, as the observer is constantly and obsequiously addressed. At some point, the life of pure representation can no longer deal with an unbending reality that refuses to flatter the viewer, and that viewer must either abandon representation and grapple with that ugly reality, or banish it altogether via increasingly beguiling and flattering representations.

Or to paraphrase another thinker on the unreal, Philip K. Dick: reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn't go away. But the American ability to make that reality go away, possibly forever, is what eclectic writer Bruno Maçães takes on his intriguing new volume History Has Begun: The Birth of a New America.

As is almost statutory for a European writer writing about America, the opening chapters are a summary tour of Tocqueville, Spengler, Hegel, Marx, Gramsci, and the various European thinkers who, to a greater or (usually) lesser extent, attempted to decipher this new American man. At this point, an American reader is apt to roll their eyes and groan “another European on tour in the US, the flip side of American backpackers with Eurail passes gawking at the Eiffel tower while getting pickpocketed. There’s going to be another postmodern deconstruction of Las Vegas, isn’t there? Maybe even a mock-heroic blow-by-blow of a Texas rodeo or WWE match.”

US-European relations, via Mad Men metaphor

At times like this, my mind rushes to that scene in season five of Mad Men when a miffed competitor verbally confronts Don Draper in an elevator, concluding with a sneering “I feel bad for you.” Draper icily retorts, “I don’t think about you at all,” leaving his downcast opponent standing there, defeated and alone.

This scene typifies the US/Europe relationship for the past half century or so: Europeans studying the pop-culture excrescences of American culture with Talmudic seriousness and delivering regular sermons, while most Americans remain content to think ‘Lithuania’ a new brand of toothpaste, or possibly an erectile-dysfunction pill.

But one would be entirely wrong to dismiss Maçães as yet another European tourist using America as a mirror on European culture (and finding the image wanting if too distinct from the original). Nor is he using America as a portal to a possible European future, for Maçães also posits the existence of a deep ideological split in the former trans-Atlantic alliance that presages disjoint futures. No, Maçães gets America, like Tocqueville (whom he liberally quotes) got it in the 19th century, which means better than most Americans did then or sadly do now.

History Has Begun really enters prescient-classic territory after all the European-with-a-Harvard-Ph.D. throat clearing about Spengler and Rawls. Right around chapter four, Maçães delineates how the society that first embraced TV as national storyteller and embarked on such extravagant fables as Disneyland, slowly allowed optional narratives to consume all of reality, even and especially on the high-stakes political plane. The Nixon/Kennedy debate—where a perspiring, unkempt Nixon lost to a bright-eyed Kennedy in the real contest, that of images—is an obvious reference point. But the illuminating contrast Maçães offers, the crux of his entire thesis, is that between that other screen-star-turned-president Ronald Reagan and the current one, Trump.

Past a certain point down the rabbit hole of representation, the roles of reality and representation flip. Or to borrow a Picasso quote: Art is the lie that tells the greater truth; the spectacle now uses truth to tell a grander lie.

Reagan used his screen presence and the television tricks of the time to make himself seem more presidential, an illusion in the service of reality. Trump however used the presidency as a continuation of his brand presence and TV show, reality in service of the remunerative spectacle. “Shoot me like I am shot on The Apprentice,” Maçães reports (through a quoted aide) as Trump saying whenever he takes the political stage. Past a certain point down the rabbit hole of representation, the roles of reality and representation flip. Or to borrow a Picasso quote: Art is the lie that tells the greater truth; the spectacle now uses truth to tell a grander lie.

And you see this everywhere.

Just about every major mainstream media story since 2016 has been an elaborate narrative built on a seed of cherry-picked truth, later shown to have been either false or greatly exaggerated. The Mueller Report, after finally being published, was not the much-ballyhooed presidential undoing. Neither was the impeachment whose imprint on the national mind was so fleeting the Democrats didn’t even make a reference to it in their national convention or in any rhetoric since. Cambridge Analytica was finally revealed to be the basket of hucksterism and journalist wishful thinking it always was. The Russian disinformation campaign’s greatest trick was convincing Western media and academic elites that their Jesus memes were (and are) an international force to be reckoned with (this plot line still has some legs to it; let’s see who wins on November 3rd).

Our political culture is littered with the unwatched pilots of new shows whose characters and plot lines bombed, whose audience never appeared, whose contracts got canceled. They’re memory-holed as quickly as a Netflix show that didn’t make it; instead, we go back to the homepage to binge or doomscroll, and an entirely different fable is there ready for you to consume.

Swipe! Swipe! Swipe! goes the smartphone screen.

Click! Click! Click! goes the TV remote.

Both Left and Right are now involved in a wrestling match for the narrative remote-control, one side wanting to switch to watching a show about Biden’s drug-addicted son, and the other claiming it’s bad movie not worth watching. Facebook and Twitter, as owners of the two TVs everyone is staring at, are wondering whether to override the remote signal and just make their own channel decision. Nobody is actually arguing about inarguable realities: it’s simply narrative warfare, a virtualized version of two speakers heckling each other, each claiming the stump in the face of a split but increasingly unruly audience, and the ruckus amplified globally via the totalizing Internet spectacle.

As one example of a lapsed narrative, take Russiagate, which has become (to borrow from Churchill) a riddle wrapped in a hacked email inside an oppo report. Let’s specifically look at ‘Russiagate Was Not a Hoax’² by Franklin Foer as a classic example of the genre. The piece is littered with the all the tropes of some convoluted whodunit: “narrative closure, “the Kiliminik story line”, “strands of speculation”, and ever on. The thing doesn’t read like investigative journalism so much as the fan wikis that sprout around cult media like Star Wars or The Sopranos: some factual framework (the ‘canon’, what is provably in the main storyline of the film or show), with endless speculative add-ons and extras from non-canonical sources. The end result is crowdsourced ‘world creation’ that’s the measure of good sci-fi: a rich and self-consistent world where a reader or viewer can imagine themselves inhabiting, and perhaps even adding to, like a game of narrative Minecraft. Those who take Russiagate seriously sound less like investigative journalists and more like obsessive fanboys; it resonates only if you too are a fan of series, and otherwise it all sounds kind of nerdy and too fantastical by half.

Of course, the Right has been on the media vanguard here for much longer than the Left. From way back in the Obama birther days (a plot line then reality-TV personality Trump promoted himself) to that most bewildering saga of our age, QAnon, the far-right has lived in a political Disneyland for even longer, pioneered it even. Which is why they excel in our current media environment, dominating distribution on platforms like Facebook, all the while indulging in yet another fantastical belief: there’s systematic censorship of right-wing media going on.

Part(!) of the QAnon diagram.

As with any narrative fandom, we’ve got the super-fans who dress up as their favorite characters in the show and LARP at special events called for the purpose. Those events are the protests that have peppered our timelines since almost COVID began. This is like the D&D nerds who grew up to become Renaissance Fair cosplayers, or those Civil War re-enactors put on a woolen képi and huff around the battlefield at Gettysburg or wherever in the summer heat. The difference is the narrative script on the left something vaguely Weimar-esque about resisting either fascism or racism, usually via civil disobedience mixed with a decent amount of rioting (such as corporate lawyers flinging Molotov cocktails at police cars).

On the other side of the Weimar LARP, the right fields militias with oddly comic-book-ish names like ‘Oath Keepers’, who appear in full battle-rattle in the middle of protests, guarding against….what exactly? The rhetoric is all about resisting government encroachment and elite domination all the while (and without skipping a beat) somehow supporting the very police and military all their weaponry is meant to defend against. Meanwhile, the blue checks on both sides adopt stirring personas of personal sacrifice in the face of overwhelming political turmoil and repression from the powers that be, always embodied by someone other than themselves³.

These paranoid hysterics from right and left are themselves an autoimmune reaction, and such reactions and can be as or even more dangerous than the potential infections that triggered them. But everyone finds the virtual or physical LARPing too fun to stop: that warm flush of moral righteousness, the reassuring centrality of your cause in the cosmic order, the heady rush of participating in ‘history’, however virtually.

A nation bonds via shared suffering and a common enemy; America instead opted for unequal suffering and making enemies of themselves.

We reach the apotheosis of Maçães’ role-play in the final chapter of the US edition of History Has Begun, when one of the deadliest and most undeniable realities of our time, COVID-19, is nonetheless co-opted as another theatrical backdrop. From its very beginnings, the virus was grafted onto such pre-existing narratives as: Silicon Valley elites and their laughable over-reacting to non-existent threats, the xenophobia of imagining we needed border controls to stop the spread (which every country eventually implemented too late), the initial media push against mask-wearing (followed soon after by the cultish insistence on wearing them everywhere including the distanced outdoors). Every take was unrelated to any scientific reality, but rather where it placed the speaker on the cratered no-man’s-land of the American political landscape (particularly with respect to the Tweeter-in-Chief). A nation bonds via shared suffering and a common enemy; America instead opted for unequal suffering and making enemies of themselves. That’s the channel we’ve opted for.

Observe how in the midst of a mysterious and deadly virus that threatened mayhem on a national scale, the show we all tuned into was what to call the thing and whether that meant you were perpetuating racism. There is no reality so hard anymore that it can’t be repurposed as backdrop in the going show.

As Maçães so ably summarized:

While in China or Italy the new coronavirus was regarded as a technical problem to be solved, in America it quickly became a great dramatic narrative. The country seemed to take its cues from movies such as Contagion. The president repeating nothing is wrong while events on the screen show otherwise, the race against the clock to avert catastrophe, the conflicts between the main characters. Comparing the reaction in the United States to that in other countries, what strikes me is how the virus is almost irrelevant. What matters is what the different characters think, say and do. The clash between those characters and between the characters and the world. Their mental conflicts. The narrative digressions: whether Trump will fire his chief medical advisor, for example. Just as in a disaster movie or television series, the epidemic provides a backdrop for action.

We’re still doing it of course.

Consider the current COVID plot elements: Many Americans still operate under the delusion that their country is uniquely failing at COVID containment, despite the European Union now far surpassing the US in new cases per capita while the continent hurtles into its second wave.

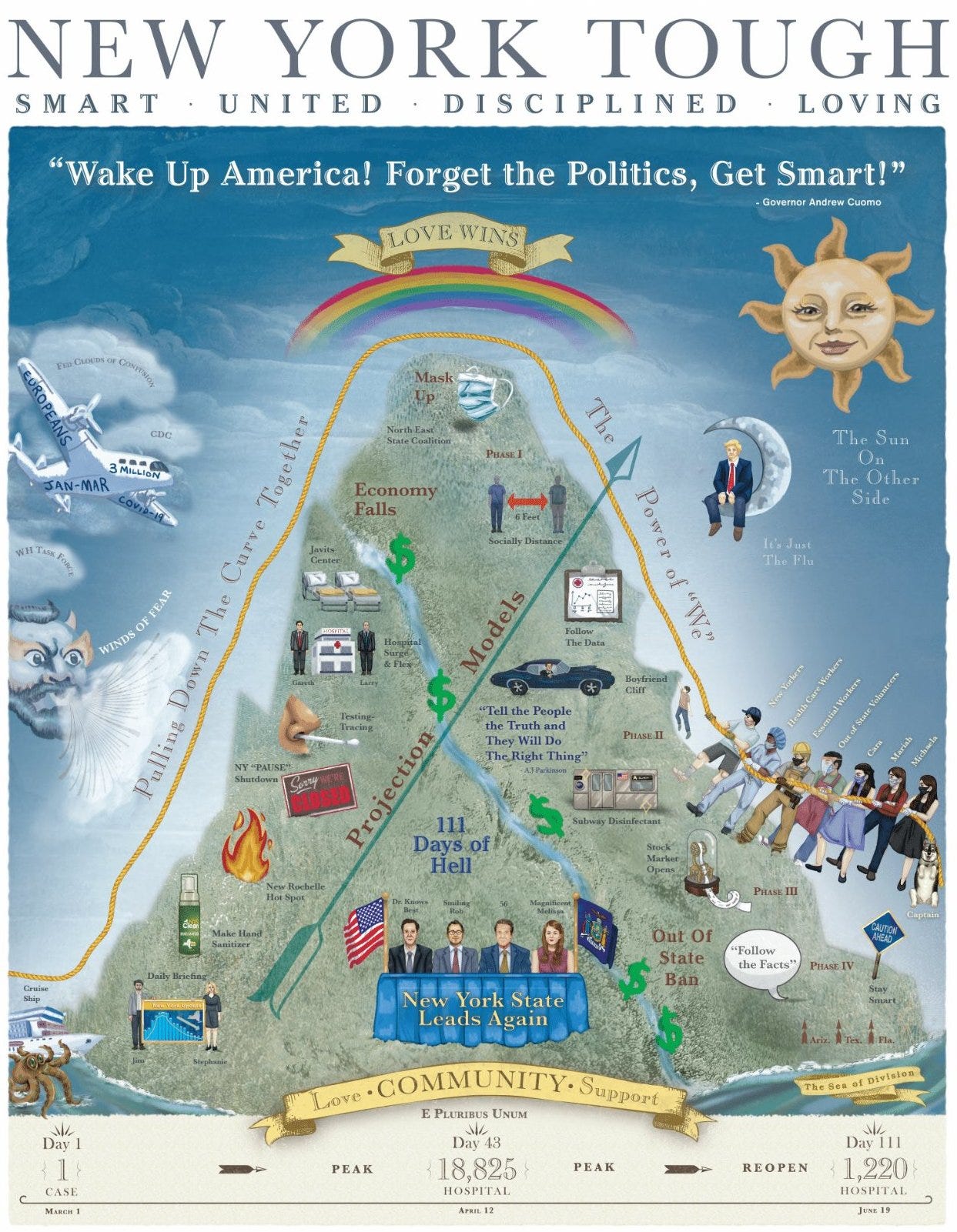

On the domestic narrative front, Andrew Cuomo, who presided over the worst COVID response in the nation, is now somehow being framed as a hero, complete with new book American Crisis: Leadership Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic and corresponding victory lap. His administration even put out a truly bizarre poster featuring the New York mortality curve—a plot representing a mountain of human death—as some sort of campy 19th-century inspirational message.

Cuomo as competent-seeming Democrat is narratively necessary as counterweight to that other incompetent, the one in the White House. Gavin Newsom, whose state fielded a response that could potentially be deemed praiseworthy, is too outside the East Coast bubble to resonate as hero figure. So Cuomo as COVID hero it is.

“Things in America felt like a disaster movie. In Europe they just felt like a disaster,” as Maçães puts it in what’s perhaps the book’s best line.

But some of us aren’t living a disaster movie, some chose yet another channel.

It was my vague suspicion, right around when panicked-COVID spring turned into COVID-lockdown summer, that maybe things weren’t actually so bad for my cohort. After boozy bouts of ‘socially-distanced’ socializing inside the polka-dot patterns of white circles on various San Francisco parks, I detected a pattern: Everyone seemed more calm, more centered, fitter-looking, and as if some weight had been lifted from their shoulders.

Intrigued, I ran a Twitter poll asking if things where better, worse, or terrible during the COVID lockdown. To my only partial surprise, 35%—fully over one-third of respondents—said their lives had gotten better under COVID.

In a confirmation of Maçães’ theory, the Zoom class of tech-enabled elites, those who could unplug from reality via representation better than anyone, largely did so. Much to corporate management’s surprise, a universal and continuing WFH didn’t ding productivity much at all. On the contrary, ‘work from home’ actually means ‘live at work’, and in well-managed companies where face time is rightly irrelevant, productivity accelerated. The stock market ripped, funding rounds closed, IPO documents were filed, hiring plans were re-booted, while everyone got more exercise and spent more time with their families. Real estate in formerly ‘second-tier’ cities like Park City, Nashville, Bozeman, and Austin skyrocketed as the American tech elite realized the ideal US living situation, once geography didn’t matter, is in a blue enclave within a red state. If there’s one reason the catastrophically failed response from national and state authorities hasn’t faced more of a backlash, it’s because the most fortunate in society, those with the wherewithal to properly demand change, were largely able to dodge it all. Reality is for the little people.

Maçães’ prophetic insight provides an alternative to the Fukuyaman theory of the historical telos: the end of history isn’t liberal capitalist boredom, a sort of global Canada, but a society disappearing into lives of pure representation, a global Twitter feed where somehow Instacart and Amazon still work. If humans ever decide to decisively stop the great wheel of history—the conquests and crusades, the nationalist fervors and manifest destinies, the cultish devotions and divine mandates—it’ll be because they were too entranced by screens to get up off the couch and give it a spin anymore. Doomscrolling finally defeated Deus lo vult! at last.

But Fukuyama, perhaps the most widely misunderstood intellectual of our time, warned that this bloodless pause would very likely not last:

Experience suggests that if men cannot struggle on behalf of a just cause because that just cause was victorious in an earlier generation, then they will struggle against the just cause. They will struggle for the sake of struggle. They will struggle, in other words, out of a certain boredom: for they cannot imagine living in a world without struggle. And if the greater part of the world in which they live is characterized by peaceful and prosperous liberal democracy, then they will struggle against that peace and prosperity, and against democracy.

For this Maçãesian post-History to last where the Fukuyaman one will not, the elite Zoom class hopes everyone prefers living inside that Zoom gallery of faces, or delivering groceries and entertainment to those who do. Reality may have inducements that even the pixel crafters and emotional engineers of Twitter and Netflix wholly lack. There may yet be those among us who, unsatisfied with the LARP, prefer the IRL joys of violence and tribal primacy—the blinding flash of the Molotov cocktail, the deafening thrill of gunshots—that blinking screens can’t quite match. Worse, there might be some looming reality even more menacing than a pandemic, that even the spectacle can’t quite mask from view. Then reality will really stop being optional.

The ‘third time’ stems from the tragedy/farce two-step in a commonly (mis)cited Marx quote: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great, world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.”

The historical context is clear from the mocking title: ‘The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’. Louis Bonaparte, self-anointed ‘Napoleon III’, had just overthrown French democracy in a bloodless coup. Marx was making a trolly comparison to Louis Bonaparte’s uncle and that Bonaparte’s much more real and eventful coup that happened on the 18th Brumaire in the final innings of the French Revolution.

I hereby propose the AGM lemma to Betteridge’s law of headlines: If a headline strongly asserts a controversial negative, the truth is actually the positive assertion.

As the child of a family that fled an authoritarian dictatorship that actually did arrive seemingly overnight via a violent revolution, the current bourgeois resistance seems remarkably incurious about the sort of things my family was obsessed with circa 1959: foreign visas, who in your circle was trustworthy or a snitch, news of who got jailed or sent to a labor camp, firearms, means of transportable wealth, how to reunite with your family on the other side of exile, burying heirlooms in the backyard before leaving with nothing but a suitcase, etc. Note to those aspiring blue-check Jean Moulins: if you’re publicly tweeting abuse at the president and getting paid to write about it at national outlets, you may not quite be the Sophie Scholl-like figure you’re imagining.

This is great. I hadn't considered the insanity of the modern world through this angle - everyone is LARP'ing all the time, without realizing it. Trying to point this out to people makes them mad because now you're 'ruining the show.'

This is a great post. Your best yet. There's a bit in Infinite Jest and DFW's subsequent interviews where he talks about lethal entertainments. The attraction of the channel we tune into overpowers other needs or futures, like living together sanely. The woke revolution and the neo-reactionary goose-steppers emerge from our many small choices to live something more exciting, and take the place of life's hard and banal work. Unfortunately, those roles are a drug and LARPing ends like a drug habit. You bottom out. You are forced to remember what war is like, and long for banality again. That's the scary part.

https://tonyreinke.com/2018/03/05/david-foster-wallace-on-entertainment-culture/